A key claim of differential privacy in [DR14] is that it provides “automatic neutralization of linkage attacks, including all those attempted with all past, present, and future datasets and other forms and sources of auxiliary information”. This is an important and often repeated claim — see e.g. [N17, Section E] and [PR23] — but the accompanying analyses are often short and assumed to be obvious. In this blog post, we investigate how DP protects against linkage attacks in some details and provide suitable qualifications that practitioners should be aware of.

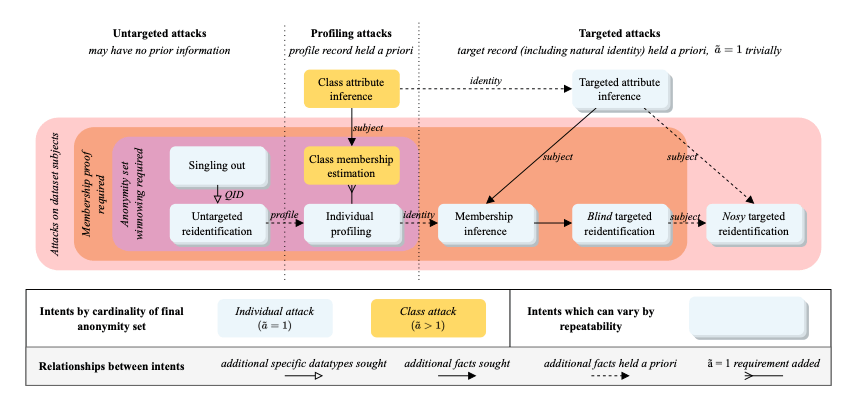

The following figure from [PR23] shows a taxonomy of linkage attack synthesised from an analysis of 94 published data privacy attacks in the literature. (It turns out that all the published privacy attacks are linkage attacks of one form or another.)

At a high-level, attacks could be targeted, untargeted, or a profiling attack. In a targeted attack, the attacker Alice has a specific individual Bob in mind and the intent is to analyse multiple datasets in such a way that a specifc set of (usually anonymised) records can be linked and shown to relate to Bob with high probability. The ultimate goal is to gather as much (private) information about Bob as possible, hence the name Targeted Attribute Inference.

Untargeted attacks share the same information-gathering goal, but the attacker does not have a specific individual in mind and would be happy to show that there exists a set of linkable (anonymised) records that, in combination, are sufficiently unique to single-out a person, no matter who that is.

Profiling attacks sit between targeted and untargeted attacks, in that the attacker has the general profile of a target in mind but does not know the exact identity of the target, and the goal is to analyse and link up multiple (anonymised) records that can be used to strengthen the profile by adding new attribute information that are consistent with the profile, ideally to such an extent that the strengthened profile has enough specificity to be linkable to a specfic individual.

Given differential privacy (DP) offers provable plausible deniability on a person’s membership in a given underlying dataset D, we can see that essentially all chains of attacks in the orange box in the taxonomy can be protected by DP. The published data could be differentially private aggregate statistics computed from the underlying dataset D, or differentially private synthetic datasets computed from D at the same level of granularity using techniques like [G11, M11, T21]. Protection against linkage attacks on these DP datasets come from the Post-processing Lemma and the Adaptive Composition Theorem, which we now briefly describe.

The Post-processing Lemma states that if an randomised algorithm is differentially private, then for all (possibly randomised) function

, the mechanism

defined by

is differentially private. In the context of linkage attacks, the function f can be thought of as linking the output M(x) with some side information followed, perhaps, by a `singling-out’ or outlier-detection algorithm. The fact that, given a differentially private mechanism M, the DP property is preserved under arbitrary postprocessing f is a key interpretation of the statement that differential privacy protects against linkage attacks using arbitrary side information.

The Composition Theorems for differential privacy [K15], in combination of the Post-processing Lemma, extend the linkage-attack protection, in the simple case, over multiple statistical data releases from an underlying dataset D and, in the k-fold adaptive case, over multiple interactive data releases from a sequence of related underlying datasets. As is usual, the protection offered by DP relies on the assumption that the dataset D being processed satisfies the condition that each row in D is sampled independently (but not necessarily from the same probability distribution) from an underlying population [KM14, YZ24].

The above are broad, general statements on DP’s utility against linkage attacks listed in the taxonomy above, based on its specific protection against membership attacks. We can take a more refined approach and look at individual attacks. The obvious place to start is the Singling Out attack, which sits at the start of the key attack chain given in the taxonomy. If we are able to show that DP offers protection against Singling Out, then DP will also offer protection against all attack chains that start with Singling Out. Here, we again have some good news.

In [CN20], the authors give a careful formalisation of the Singling Out notion stated in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), whereby an adversary is said to predicate single out a dataset D using the output of a data-release mechanism M(D) if the adversary manages to find a predicate (aka boolean function) p matching exactly one row x in D with probability much better than a statistical baseline. The authors then show that DP mechanisms are secure against predicate singling out attacks, but the more traditional approach k-anonymity is not. The catch, as with differential privacy mechanisms in general, is that the correctness of the proof relies on the assumption that the records in dataset being analysed are sampled independently from an underlying population, an assumption that must be carefully verified in practice.

References

- [DR14] C. Dwork, A. Roth, The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy, NOW Publishers, 2014

- [N17] K. Nissim, et al, Bridging the gap between computer science and legal approaches to privacy, 2017.

- [PR23] J. Powar, A.R. Beresford, SoK: Managing risks of linkage attacks on data privacy, PET, 2023.

- [G11] A. Gupta, M. Hardt, A. Roth, J. Ullman, Privately releasing conjunctions and the statistical query barrier, STOC, 2011.

- [M11] N. Mohammed, et al, Differentially private data release for data mining, SIGKDD, 2011.

- [T21] Y. Tao, et al, Benchmarking differentially private synthetic data generation algorithms, 2021.

- [K15] P. Kairouz, S. Oh, P. Viswanath, The Composition Theorem for Differential Privacy, ICML, 2015

- [KM14] D. Kifer, A. Machanavajjhala, Pufferfish: A framework for mathematical privacy definitions, TODS, 2014

- [YZ24] S. Yang-Zhao, K.S. Ng, Privacy preserving reinforcement learning over population processes, 2024.

- [CN20] A. Cohen, K. Nissim, Towards formalising the GDPR’s notion of singling-out. PNAS, 2020.